Have we learned the buttercup’s lesson yet? Are our hands off the very blossom of our life? Are all things – even the treasures that He has sanctified – held loosely, ready to be parted with, without a struggle, when He asks for them?” Parables of the Cross

Lilias calls attention to three stages of the buttercup’s life: the bud with petals tightly clasped in the calyx; the young flower, loosening somewhat in the daytime, while retaining the power of contracting its petals; an open flower, petals folded back, golden crown, beyond the power of closing.

Then, noting the central flower pictured above – wide open; fully exposed – she raises the question: “Have we learned the buttercup’s lesson?” The lesson, she goes on to state, is one of total abandonment to God, like the open flower, ready to release all things when asked to do so: “Are all things – even the treasures that He has sanctified – held loosely, ready to be parted with, without a struggle, when He asks for them?”

Abandonment to self. Full surrender. These phrases capture a concept which, frankly, runs counter to our culture’s most cherished beliefs: Autonomy. Independence. Self-determination. Personal identity. These concepts – and many more along these same lines – are not only highly esteemed values of our western society but, for that matter, our human nature. “Mine” and “me” are included in the short list of the earliest words of a toddler’s vocabulary

But what if. . . what if abandonment – “letting go” – is release to something, Someone better? If I truly believed that to be the case, would it make any difference?

Throughout the many years researching the life and works of Lilias Trotter, I was dogged by a question: “Was it worth it?” Did she really need to give up – “let go” – of a career in art that potentially could have ranked her among the great artists of her day? Isn’t it possible that she could have reached more people for Jesus through her great gift (and potential fame) than she did in the relative obscurity of North Africa, around people who did not recognize her immense talent, for whom her art had little or no currency?

It was that very question that I was forced to answer in the home of her grand-nephew many decades after her death. Gracious hosts, Robin and Claire shared their home, their hospitality and showed us various Trotter artifacts that had come their way as family historians. At the end of our visit, Claire looked me in the eyes, and echoed my question: “Why? Was it worth it, really? She gave so much for so little return.”

I breathed up a silent prayer and drawing from all I knew about Lilias – her life, her call – admitted, first, to empathizing with her questions. Then I went on to observe the high regard we give people in other professions – artist, athlete, musician by way of example – who sacrifice everything for the development of their discipline . How we recognize – admire – their singleness of purpose. We call it “passion.” Yet, when the same devotion is given to world of the spirit – faith – we call it “fanaticism.” Lilias, I noted, was fueled by her love for a particular people: their lot on earth; their destination eternally. If we believed the stakes to be eternal, as did Lilias, could we not acknowledge the nobility of her mission?

I know that Lilias’ “lesson of the buttercup” was born of personal experience – a lesson fully embraced. Even as she beautifully illustrated the process by which one attains to this level of detachment I recognized how she, personally, had come to that level of total abandonment where it was no longer sacrifice, but joy, to be set free to follow her Master’s purposes – whatever wherever that might be. Many of us remain in that transitional state, opening our petals for a while, but retaining our power to contract them.

The Lesson of the Buttercup – Lilias’s lesson – is a gentle one. It is a gradual movement from tight control, to conditional release, to full abandonment. It is, at core, a lesson of trust. It is the belief that our Creator, the One who gave us all that is good in our lives, knows better how to use those “gifts” for His Higher purposes and for our highest good. It is less a matter of what we give up and more a matter to Whom we release it.

C. S. Lewis puts it this way: “The principle runs through all life from top to bottom. Give up yourself, and you will find your real self. Lose your life and you will save it. Submit to death, death of your ambitions and favourite wishes every day and death of your whole body in the end: submit with every fibre of your being, and you will find eternal life. Keep back nothing. Nothing that you have not given away will be really yours. Nothing in you that has not died will ever be raised from the dead. Look for yourself, and you will find in the long run only hatred, loneliness, despair, rage, ruin and decay. But look for Christ and you will find Him, and with Him everything else thrown in.” (from Mere Christianity)

Lilias learned the “lesson of the buttercup” early on. She looked back, decades later, and rejoiced at the wonderful life God had given her. I don’t know fully what the “lesson of the buttercup” means for me in the large. It certainly has not required, to date, anything close to radical, as with Lilias. But I do have a fairly good idea what it means for me today: to entrust my life, and all the people, places, plans, things that define it, fully into God’s loving and trust-worthy care.

“He is no fool who gives what he can’t keep to gain what he cannot lose.”

Jim Elliot

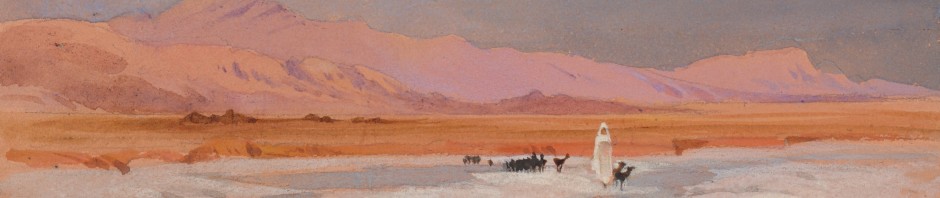

Watercolor: Color plate from Parables of the Cross

A friend of mine told me to notice Mary’s hand in the Pieta by Michelangelo. Her hand is open–she receives from the Lord even in her pain. Just liket he butter cup.